The Harpole Burial: One year on

A year on from the discovery of what is believed to be the one of the most significant early-medieval female burials ever uncovered in Britain, investigations continue on this remarkable find. After months of painstaking work in the lab, our specialists have cleaned many of the delicate items. Our team have also been micro-excavating blocks of soil lifted during the excavation, unearthing exciting new details about the burial.

The Harpole Burial – named after the nearby village of Harpole, Northamptonshire – was first discovered in 2022 during archaeological works ahead of a Vistry Group housing development, supported by Archaeological Consultants, RPS (A Tetra Tech Company). It was reported to the Coroner as a potential Treasure, and the normal legal process is ongoing.

Exploring the incredible necklace

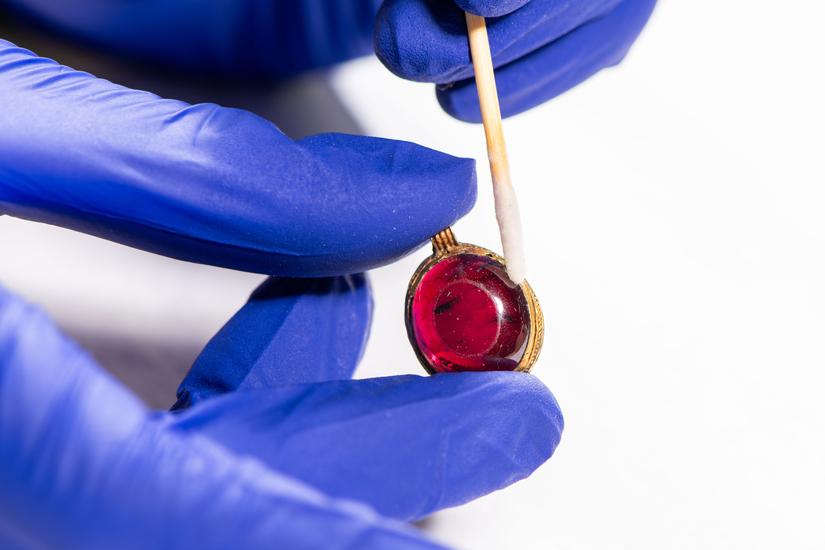

We have now fully cleaned many of the 30 pendants and beads, which make up an extraordinary gold, glass and gemstone necklace buried with the deceased. This has revealed the full glory of this artefact - exposing the intricate gold work and rich colours of the semi-precious stones and multicoloured glass previously hidden by soil.

Our specialists can now examine all parts of the necklace in more detail and try to answer questions about how it was made. One key question is whether the coin pendants are original Roman coins or imitations made specifically for the necklace.

Micro-excavating unique silver cross

Painstaking micro-excavations - a technique where whole blocks of soil are lifted from a site to be excavated under controlled lab conditions - of a large cross, first seen on an x-ray image, have successfully revealed part of its surface. We can now begin to fully evaluate this unusual item.

A central cross is decorated with a smaller gold cross, which has a large garnet and four smaller garnets. At the end of each arm are smaller circular crosses made of silver, with garnet and gold centres. These are very similar to the pectoral crosses found in other high status female burials from this time, including the Trumpington burial. The use of these crosses within one larger cross, however, is unique and suggests the individual may have held a very special position within the Christian community.

Through micro-excavating the feature, our conservators have revealed it is mostly made of extremely thin sheets of silver attached to wood, its corroded surface barely distinguishable from the surrounding soil. We hope to identify the type of wood used, and better understand how the cross was constructed.

Analysing human remains

Whilst initially it was believed only a few fragments of teeth had survived, work on another soil block has unearthed further fragments of the individual’s skeleton. Our osteologists have identified the upper part of a femur, part of the pelvic bone, some vertebrae and part of a hand and wrist. These lay underneath a crushed copper dish placed within the grave – the metal slowing the decay of the 1,300 year-old organic material.

We currently believe that these are likely to be the human remains of a woman, based on comparable burials from the period. Early analysis indicates the skeleton belonged to a young adult, which also matches other high status female burials from this period. Through further tests, we hope we can reveal details such as where she grew up and confirming biological sex.

Work continues…

Our specialists are continuing to analyse and piece together the story of the Harpole Burial. As well as getting a better understanding of the items recovered and individual buried, it is hoped that scientific techniques may reveal more about funerary rituals at the time. This potentially includes studying tiny fragments of organic matter, which may hold clues as to what the person was wearing and the types of materials they were lying on.