The ‘world’s most difficult jigsaw puzzle’: a once in a lifetime discovery from Roman Southwark

Further research on finds from our excavations ahead of the ‘Liberty’ development by Landsec in Southwark has led to an incredibly exciting ‘once in a lifetime’ moment for our Senior Building Material Specialist Han Li, and hit the headlines across the world this morning.

Among the remains of an early Roman building, demolished at some point before AD 200, was one of the largest collections of painted Roman plaster ever discovered in London - on the same site where we have already uncovered stunning mosaics and a rare mausoleum.

These beautiful frescoes once decorated around twenty internal walls of the building; however, the enormity of our find wasn’t immediately obvious. That’s because the decorated plaster was found dumped in a large pit, shattered in thousands of fragments – the result of Roman demolition works to clear the old building.

Han Li has spent months laying out all the fragments and painstakingly piecing the designs back together. Describing the process, he said:

This has been a ‘once in a lifetime’ moment, so I felt a mix of excitement and nervousness when I started to lay the plaster out. Many of the fragments were very delicate and pieces from different walls had been jumbled together when the building was demolished. It was like assembling the world’s most difficult jigsaw puzzle.

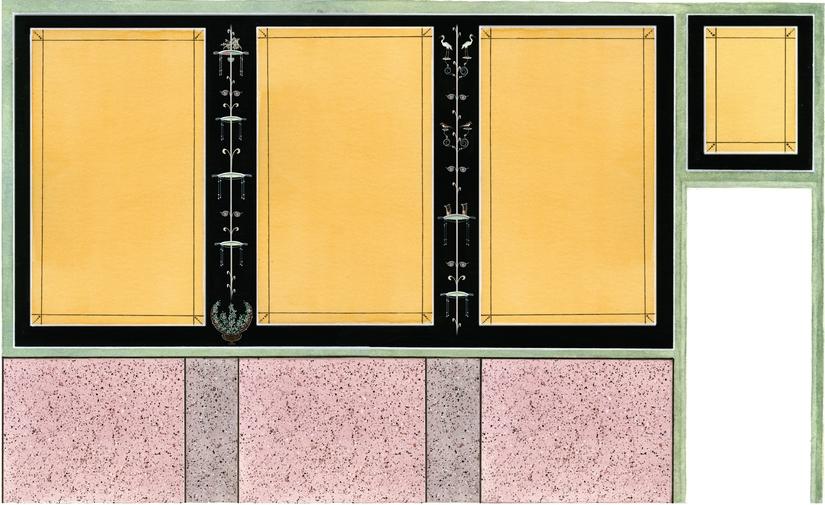

Slowly, designs began to appear which were last seen more than 1800 years ago. Bright yellow panel designs with black intervals. images of birds, fruit, and lyres (stringed instruments similar to harps).

Thanks to Han’s work, as well as advice, opinions and resources from our specialist teams, and external colleagues including Ian Betts and the British School at Rome, our Senior Illustrator Faith Vardy has been able to start reconstructing these vibrant artworks to reveal their full glory.

The group or groups of painters responsible for creating these frescos took inspiration from wall decorations in other parts of the Roman world – such as Xanten and Cologne in Germany, and Lyon in France. These paintings were designed to show off both the wealth and excellent taste of the building’s owner or owners.

Some fragments imitate high status wall tiles, such as red Egyptian porphyry (a crystal speckled volcanic stone) framing the elaborate veins of African giallo antico (a yellow marble). Styles like these have been found north of the river in Londinium, in Colchester, Germany, and Pompeii. While panel designs were common during the Roman period, this yellow panel scheme is a rare discovery. It has been identified at only a few sites in the country, including Fishbourne Roman Palace - one of Britain’s most luxurious Roman residences.

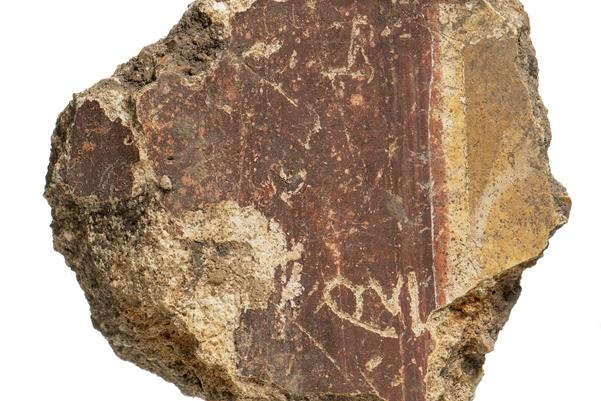

Even more excitingly, among the fragments is a tangible link to one of the artists who created them: the remains of their signature – the first known example in Britain. This is framed by a tabula ansata, a carving of a decorative tablet used to sign artwork in the Roman world. It contains the Latin word ‘FECIT’ which translates to “has made this”. Tragically, the fragment is broken where the painter’s name would have appeared, meaning their identity will likely never be known.

The plaster also reveals traces left behind by the building’s owners and visitors – in the form of ancient graffiti. This includes an etching of a near complete Greek alphabet – the only known example of this inscription from Roman Britain – other examples in Italy suggests that the alphabet served a practical use, such as a checklist, tally or reference. The skilfully scored letters suggest that it was done by a proficient writer and not someone practicing their writing.

Other similar examples of Greek alphabet graffiti in Italy suggests that it had a practical use, such as a checklist, tally or reference. We’re still investigating exactly what the building was used for, but this discovery suggests it may have been a partly commercial property, perhaps relating to the storage or distribution of storage jars and vessels, brought to London by ship from the wider Roman empire.

Close study and analysis of the thousands of fragments has revealed more graffiti and even painter’s guidelines, as Han Li explains

These were often very difficult to see as they had been buried for nearly two millennia. But if the light is just right, some very surprising images are revealed. These discoveries act as a window to the everyday past.

One fragment has what looks like a crying woman with her tears dripping down her face. Her hairstyle looks like it may date to the time of the Flavian dynasty (AD 69-96).

Another looks to be the painter’s guidelines of a petalled flower within a circle; it appears that this was scored into the plaster with the help of a compass. The painters likely changed their mind and chose not to paint it.

Explore other graffiti and inscriptions found among the wall plaster fragments

Work to further explore each piece of plaster continues, including comparing the Liberty wall paintings to others from Britain and the wider Roman world. The results will be published and fragments archived for future study, as well as made available for temporary or permanent display.

Archaeological investigations at The Liberty are being carried out by MOLA on behalf of Landsec, Transport for London (TfL), and Southwark Council.