Unique burial thought to be rare direct evidence of slavery in Roman Britain

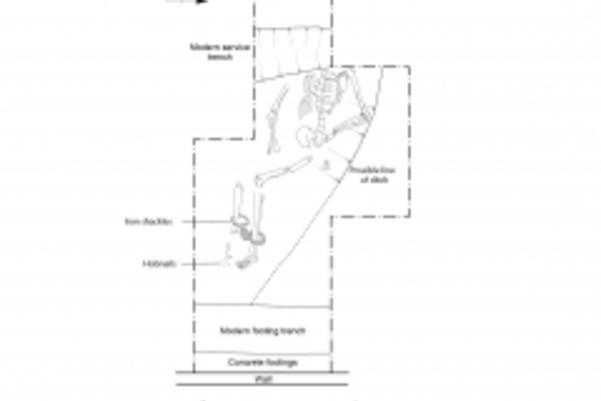

Archaeologists from MOLA have been researching the skeleton of an adult male found buried in a ditch, secured at the ankles with a locked set of iron fetters. This is the first discovery of a burial wearing this form of restraint from Roman Britain, raising questions about who this person was and why they were shackled.

Discovered by builders working on a home extension in Great Casterton, Rutland, radiocarbon dating undertaken by Leicestershire Police showed the remains to date from A.D. 226 to 427. MOLA archaeologists were brought in to fully expose, record and analyse what is now recognised to be an internationally significant find. The results have been published today in the journal Britannia.

Evidence of enslavement?

Slavery was commonplace in the Roman Empire and the practice is described in written sources from the time. However, identifying enslaved people in the archaeological record can be difficult. For this period, iron shackles are one of the only artefacts that have a strong direct link to slavery and have been found on archaeological sites across the Roman Empire. Shackles are very rarely found with human remains and the Great Casterton discovery is the first burial of a man wearing lockable ankle fetters identified from Roman Britain.

There are a small number of burials that have been found in the UK with heavy iron rings around the limbs and some of these individuals had also been beheaded. However, unlike the Great Casterton fetters, these rings, some of which may have been forged onto the bodies, probably could not have been functional restraints worn in life. They might have been added in death and it is, therefore, possible that they are symbolic shackles meant to demean the dead or brand the wearer as a criminal or slave in the afterlife. A few Roman written sources also mention the use of iron restraints to prevent the restless dead from rising and influencing the living.

What do we know about the man buried at Great Casterton?

To help build a picture of the life and identity of the man buried at Great Casterton and to try and understand the significance of the fetters, MOLA’s experts undertook detailed research. Examination of the skeleton suggests the man led a physically demanding life. A bony spur on one of the upper leg bones may have been caused by a traumatic event, perhaps a fall or blow to the hip, or else a life filled with excessive or repetitive physical activity. However, this injury had healed by the time he had died, and the cause of his death remains unknown.

Studying the burial itself, the awkward burial position - slightly on his right side, with his left side and arm elevated on a slope - suggests he was buried informally, in a ditch rather than a proper grave cut. Although there is a Roman cemetery just sixty metres away, it seems that this person was buried just outside – perhaps a conscious effort to separate or distinguish them from the people buried within the cemetery.

The identity of the man from Great Casterton will never be known for sure, although together, the various pieces of evidence present the most convincing case for the remains of a Roman slave yet to be found in Britain. Intriguing questions remain, why, for example were this man’s fetters not removed to be reused? Whether or not the man had been enslaved during life, the manner of his burial could represent a form of deliberate mistreatment of his body and likely indicates ill will from those who had power over him at the time he died.

MOLA Archaeologist Chris Chinnock said:

“The chance discovery of a burial of an enslaved person at Great Casterton, reminds us that even though the remains of enslaved people can often be difficult to identify, that they existed during the Roman period in Britain is unquestionable. Therefore, the questions we attempt to address from the archaeological remains can, and should, recognise the role slavery has played throughout history.”

MOLA Finds Specialist Michael Marshall said:

“For living wearers, shackles were both a form of imprisonment and a method of punishment, a source of discomfort, pain and stigma which may have left scars even after they had been removed. However, the discovery of shackles in a burial suggests that they may have been used to exert power over dead bodies as well as the living, hinting that some of the symbolic consequences of imprisonment and slavery could extend even beyond death.”

Read the full journal article about this research, 'An Unusual Roman Fettered Burial from Great Casterton, Rutland', here.