Flints, glorious flints

We’re carrying out archaeological excavations in South Marston, Wiltshire, on behalf of Orion Heritage and Taylor Wimpey. This is the third in our series of blogs following the dig’s progress and sharing updates from the field.

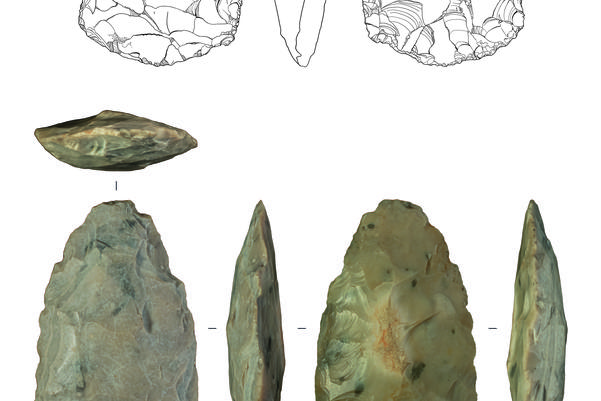

If you’re a regular reader of our blogs, you’ll know that we recently made an unexpected discovery at South Marston. So far, our excavations showed that the earliest activity on this site dates to the Iron Age (750 BC – AD 43) and Roman (AD 43 – 410) periods. But buried in one of the site’s many ditches was a beautiful late Neolithic axe-head. We finished our last blog with a question – how did this ancient axe-head end up in an Iron Age ditch?

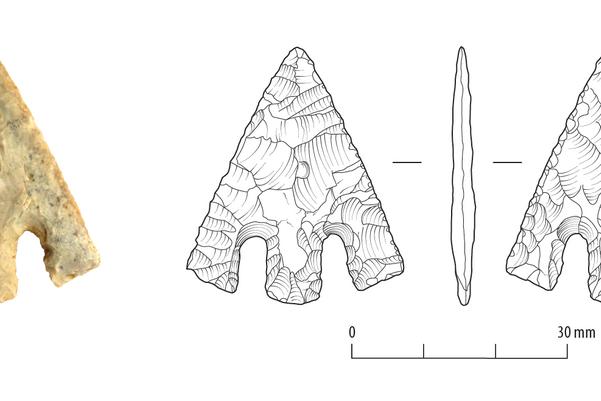

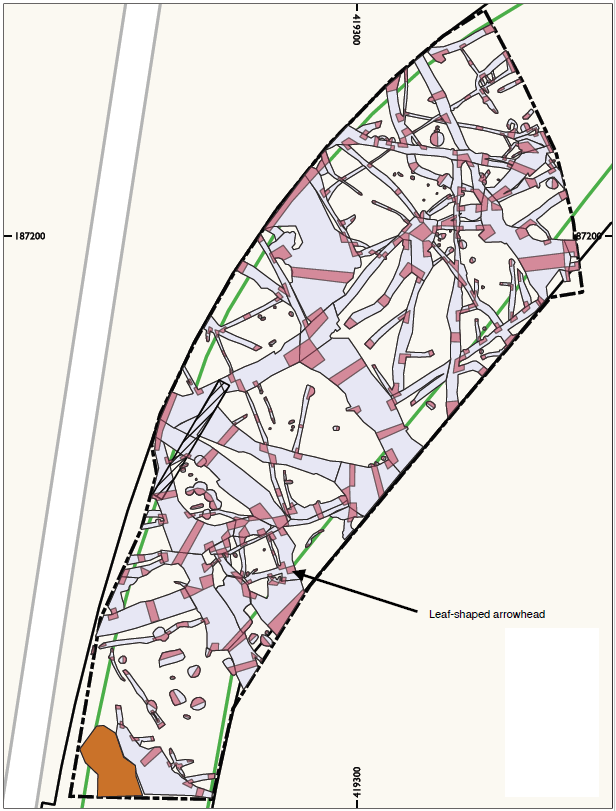

While we still don’t have a definite answer, excitingly, we have uncovered another piece of the puzzle, this late Mesolithic - early Neolithic (4100 – 3800 BC) leaf-shaped arrowhead.

Just like the axe-head, the ditch where our arrowhead was found only dates to the late Iron Age and Roman British period. While both may have ended up in the ditch naturally over time, it does suggest they may have been found by the site’s Iron Age residents and placed into the ditches as part of a ritual activity. They would have recognised both pieces as tools, just like we do today, and likely understood that they came from a long time ago.

This is just a theory for now, but what this arrowhead does tell us how South Marston’s landscape was used during the late Mesolithic and early Neolithic periods, between 7000 – 3800 BC.

Late Mesolithic and early Neolithic life in South Marston

This is a time where life across Britain was changing, from nomadic hunter-gathering to landscape management and, eventually, farming. The people of the late Mesolithic and early Neolithic periods created woodland clearings which attracted large grazing animals such as deer and aurochs (an extinct ancestor of modern cattle). This meant communities could camp and hunt nearby, rather than having to constantly follow the herds.

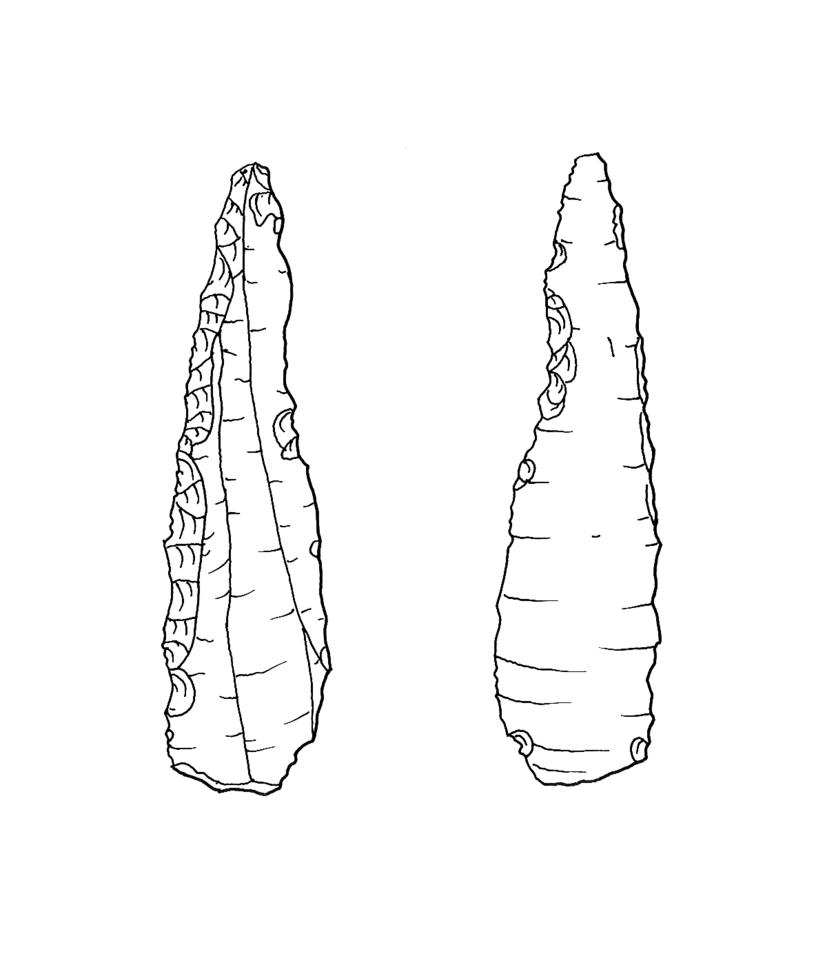

However, they couldn’t get as close to the animals in the open clearings as in woodland. This meant that the standard Mesolithic arrowhead – a very small flint called a microlith – wasn’t good enough.

Things had to change, and in the early 4000s BC leaf-shaped arrowheads, just like the one we found at South Marston, were invented. These were bigger and heavier than the microliths, but their streamlined shape meant the arrow could fly through the air easier, quicker, and further.

How to spot a flint tool

These fascinating stone tools are our only evidence, so far, of South Marston’s earliest residents. They’re also the type of archaeological object you might be lucky enough to find while out on a countryside walk or even digging in your back garden! So, how do you know if you’ve found one?

Read on to find out – we’ve illustrated this guide with sketches and photographs of flint tools we’ve uncovered at our excavations across the country, so you can see the full range of these ancient tools.

Here are some clues that can help you tell if a piece of flint has broken naturally or if someone made it into a tool. All flint tools will have at least one or two of these, but they might be hard to spot at first.

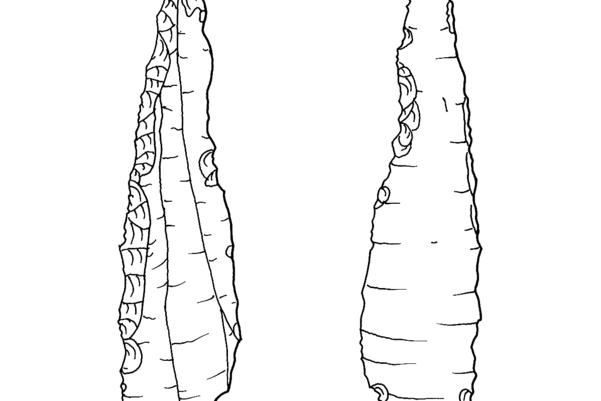

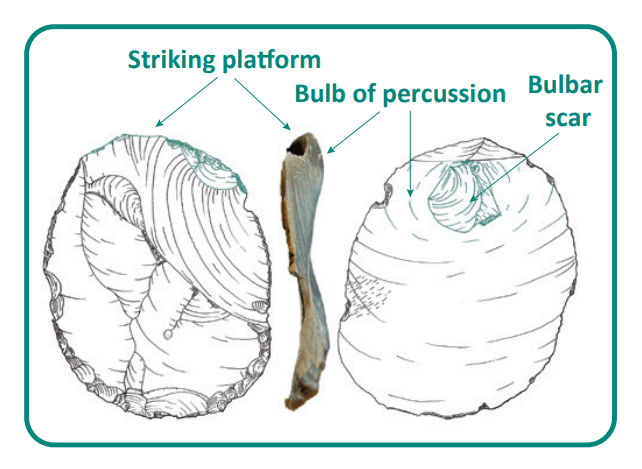

Making the first blow: can you spot a striking platform or bulb of percussion

Striking platform: a flat place where flint is hit with a hammer made from stone, bone or antler to start shaping it into a tool.

Bulb of percussion: a lump made when the flint is hit. There might also be a small chip of flint missing – this is called a bulbar scar.

Making waves: look for ripples on the flint

When flint is hit with a hammer, it makes a shock wave through the flint. This makes pieces of flint flake and fall off. It can also leave waves or ripples on the flint.

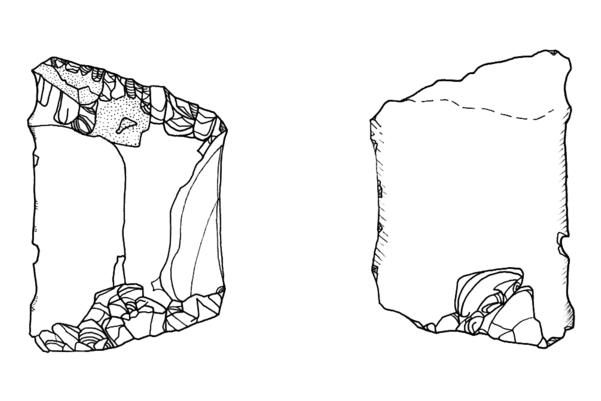

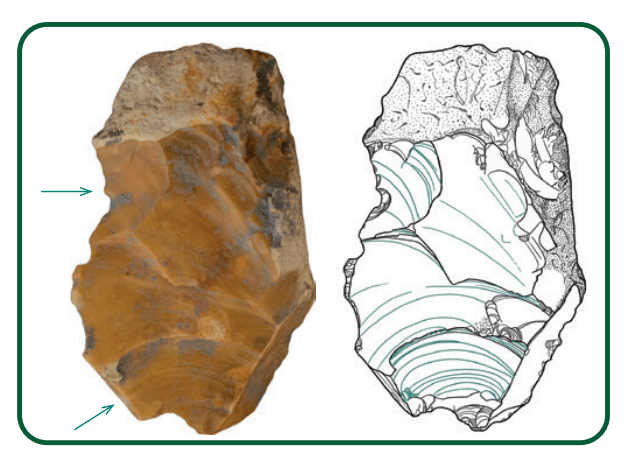

Making changes: has the flint been reshaped

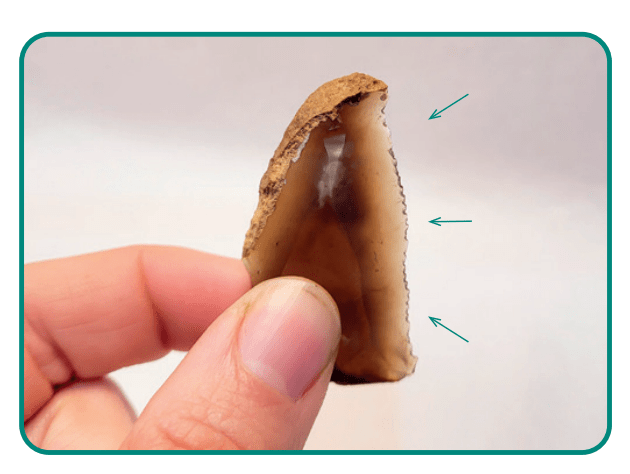

Flint tools were made to last, but they had to be reworked to keep them sharp (or blunt). They could even be made into a totally different tool by carefully chipping away small pieces of flint. Can you spot where this flint has been sharpened over time?

What colour is your flint

When flint is heated in a fire, it can turn light grey, white or even pink. Flint wasn’t just used for making tools. If you find a flint that looks like this but doesn’t show other signs of being made into a tool, it could have been heated in a fire and used to keep water warm. Of course, flint can also be used to light fires.