Getting to the bottom of the Glenfield Park cauldrons

Conservation and scientific analysis work on a group of 11 remarkable Iron Age cauldrons uncovered at Glenfield Park continues to shed light on the construction and repair of these impressive metal objects. Thought to date to the 4th-3rd centuries BC, the ancient artefacts were found in 2013 at an archaeological site on the fringes of Leicester by a team from ULAS.

Investigations have revealed that at least four of the five cauldrons examined to date have a separate, copper alloy base piece riveted to their bottom. This is not the first time this feature has been observed – for example many of the Iron Age cauldrons excavated at Chiseldon in Wiltshire in 2005 were also found to have one or more separate pieces forming the base.

This trait is particularly interesting because it is a common feature but its purpose is not always clear. It could represent repair work, following common damage caused through years of use, but there are other possibilities: might this be a repair carried out during the manufacturing process? – Analysis of the Glenfield cauldrons examined so far shows that their metal was hammered out as thin as up to 0.2 of a mm so it is easy to see how vulnerable this would make them to damage while they were being made - or could it even be a design feature, added intentionally from the start?

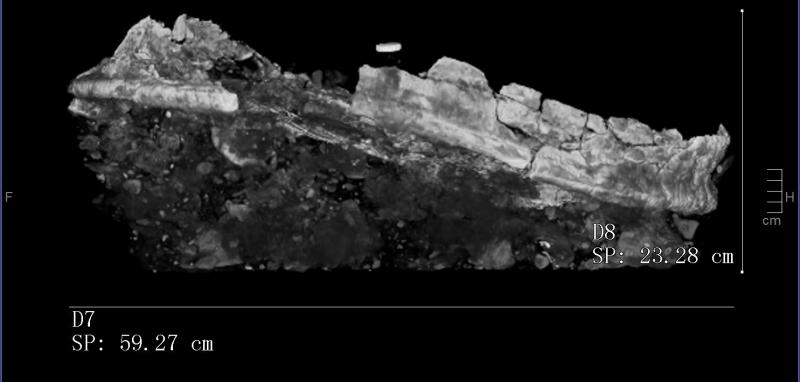

The most recent cauldron to be micro-excavated proved challenging; like all the Glenfield Park cauldrons it was heavily corroded and set in hardened clay soil. CT scans showed this one was deposited upside down, had been pushed down through its rim and was crushed almost flat, with a large area of loss on one side.

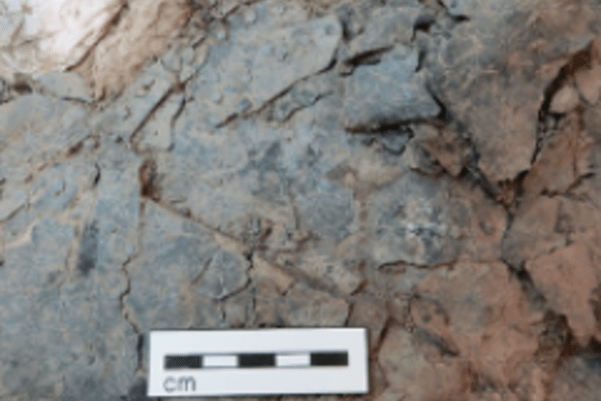

However, with great care, our conservation team has been uncovering key details to understand more about what happened to it before it went into the ground. What remains of the bases of some of the first cauldrons to be examined suggested that they had a relatively regular-shaped, roughly circular edge to the base piece join on both sides. This cauldron (seen in the video below) showed something different.

Part of the upper section of the bowl ends in a surprisingly ragged lower edge, one end of which seems to have been cut to extend outwards beyond the curve of the join. On turning the cauldron and excavating the exterior, the picture became clearer: the separate base piece was attached to the outside, its edge and riveting corresponding to the ragged edge on the interior and ancient tears to the base piece.

The uneven edge at the join – contrasting greatly with neatly finished edges elsewhere on the cauldron – strongly suggests there has been some serious tearing to an area near the bottom of the cauldron and the join has repaired this. This helps support the view that such base pieces were added as repairs rather than as a decorative feature.

Analysis by scientists at the British Museum of samples taken from the upper section and first base piece indicate that the composition and microstructure of both sections are similar enough to have been worked from the same cast blank. This means it is very likely that the bottom of the cauldron was cut off and riveted back on as a neat way to mend a torn base.

As micro-excavation continued, another surprise; the remains of a second base-piece was uncovered, a smaller, roughly circular piece, running parallel below the first. Analysis shows that this piece has a different microstructure to the first base piece and the rest of the copper alloy bowl, so it is likely that it did not come from the original cauldron bowl. Perhaps in the area lower down the damage was too great to save the bottom and a new piece had to be added.

We cannot yet tell for sure when these repairs took place. Was the base cut off and reattached and a piece added to the bottom while it was being made, or sometime later after the cauldron had been in use? Both are possible. It’s equally possible that the first base piece was reattached and the lower base piece added much later.

What seems clear is that the fabric of these cauldrons was valuable enough to be worth reusing if possible in the face of damage, rather than throwing away and starting again. Also, that although new pieces could be added, these Iron Age craftspeople sometimes chose to use the same piece from the bottom of the cauldron, cut off and riveted back into place. This seems easier than working a new piece into shape for large areas and re-cutting the base would have saved precious resources. In fact, if an appropriate replacement was unavailable, this could also have been the only option.

Work on the assemblage continues and our understanding may continue to develop and take new directions as we continue to reveal the secrets of these very special vessels.

The Glenfield Park Project is funded by the developer, Wilson Bowden Developments Ltd. For more information about the cauldrons and their discovery visit the ULAS website.