SEGRO Dig Diary 1 - the school and alms houses

We’ve been digging at SEGRO Park Wapping, ahead of development which will transform this site into the next generation of urban warehousing for Central London. As part of discharging pre-start planning conditions for the site, between September 2024 and May 2025 our team of archaeologists excavated and recorded a wide range of archaeology, and we’ve now submitted all the findings as part of our post excavation programme.

A school, the alms houses, and the coopers

The main activity on this site took place during the early modern period (1500-1800). Our excavations have revealed the remains of a chapel, alms houses, and a school building. The team have also excavated rows of terraced housing and associated features, including brick-lined cesspits filled with rubbish from local pubs, wells, and soakaways.

We’ve been digging into the historical records to uncover more about these…

The first documented building on our site was a free school for poor boys and alms houses for poor, older people to live in. They were founded in 1536 by Nicholas Gibson who was a sheriff of London (this was an important elected position; the sheriffs were responsible for organising law and order – before London had police – and collecting taxes). In 1553 Nicholas’ widow Dame Avice Knyvet gave more money to support the school and alms houses. She asked the Worshipful Company of Coopers to look after them for her – the school still exists today, although it has now moved to Upminster.

The school and alms houses are first recorded in John Stow’s 1598 survey of London as “for the instruction of sixty poor men’s children, a schoolmaster and usher with fifty pounds... also... alms houses for fourteen poor aged persons, each of them to receive quarterly six shillings and eight pence the piece for ever.”

Who were the Coopers?

Coopers make and repair wooden casks and barrels – this isn’t a well-known job today, but it was very important in the past because everyday goods, such as alcohol, meat, fish, flour, and sugar, were stored and transported by barrel. The Worshipful Company of Coopers has existed in London since the 1400s and used to control all barrel making in the city. Booming global trade from the 1500s onwards meant lots of barrels were needed and the coopers became very wealthy. They used their money to support charities and education – like the school and alms houses. The Worshipful Company continues this tradition today.

Some of the soakaways and pits we found here were lined with old wooden casks – a nice connection to the former occupants of this site!

The school

We don’t often find archaeological objects we can directly link to children, but here we were delighted to find evidence for both schoolwork and play.

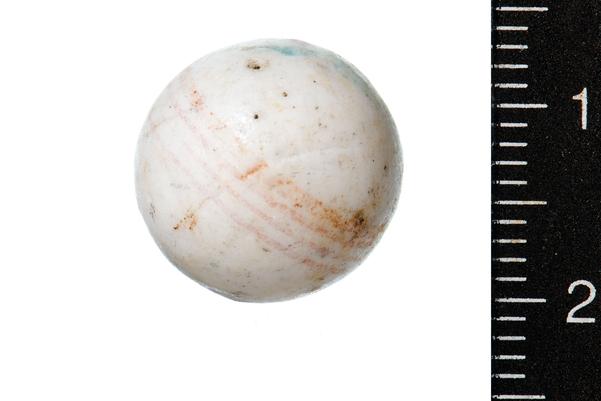

Alleys

These ceramic alleys (marbles designed to look like they were made from alabaster stone) were found in a covered, brick lined drain – perhaps they were lost during a breaktime game!

School tablets and slate pencil

This is the corner of a reusable slate tablet, and the pencil used to write on it. Children would have used chalk or slate pencils to copy down from the blackboard or practice their handwriting and rubbed them clean for the next lesson. Can you spot any letters or names scratched into them?

The alms houses

The early residents of the Cooper’s alms houses were likely older widowed women. Living here would have given them a home and a community, as well as provided living expenses they may not have been able to afford themselves. Each received six shillings and eight pence, four times a year – equivalent to about 11 days wages for a skilled tradesperson.

They might also receive money from wealthier locals, such as in 1655, when a widow from Stepney called Elizabeth Greene left them money in her will:

I give and bequeath unto the Fourteene widdowes living in [seven?] Alms houses in Schools house yard being the Coopers Alms houses To each of them Two shillings and Six pence

The alms houses also appear in John Stypes’ ‘A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster’, an expanded version of John Stow’s survey, published in 1720. By this time the number of people living here had risen to twenty –fourteen women and six men – each had a room, a cellar, and a small garden. The women received 20 shillings, four times a year, this was broadly equivalent to the six shillings and eight pence they were given in the 1500s, while the men got 25 shillings.

We can also get a glimpse into the lives of people in the alms houses through later census records.

The 1871 census includes Sarah Bloomfield, a 69-year-old widow, and Adelaide Brown, a 66-year-old widow. Looking back to the previous census taken in 1861 we can see both women were living with their respective nieces and nephews – and in Adelaide’s case with her 5 great nieces and nephews all under the age of 10! Moving into the alms house was probably very relaxing for her.

Other alms women had unmarried female relations living with them. Elizabeth Partis lists her cousin, 20-year-old Sarah Weston who was born in Sheffield, Yorkshire, as a domestic servant. Meanwhile Sarah Hartford, a 78-year-old widow from Greenwich lived with her daughter, Emma Stedman, who was born in Stepney. Both Sarah and Emma were working as vest (waistcoat) makers.

Cooper’s connections

While all residents were required to have connections to the area or the charity to live in the alms houses, these are not always clear. However, we can see several residents on the 1871 census had direct links to The Worshipful Company of Coopers.

These include:

- Mary Price, a widow who appears on the 1851 census living with her parents, who were then in their 70s. Her father Thomas Toone lists his occupation as Coopers’ Manager.

- Mary Alexander, the 1861 census tells us her husband James (from Scotland), and her sons David and William, were all coopers.

- Robert Clarke, who lived in the alms house with his wife Isabella, and George Teasdale, who lived with his wife Elizabeth. Both men appear as coopers on the 1841 and 1851 censuses.